Trump is backing down—or appears to be. What’s the best response?

Recent history suggests that the retreat is tactical, not transformational.

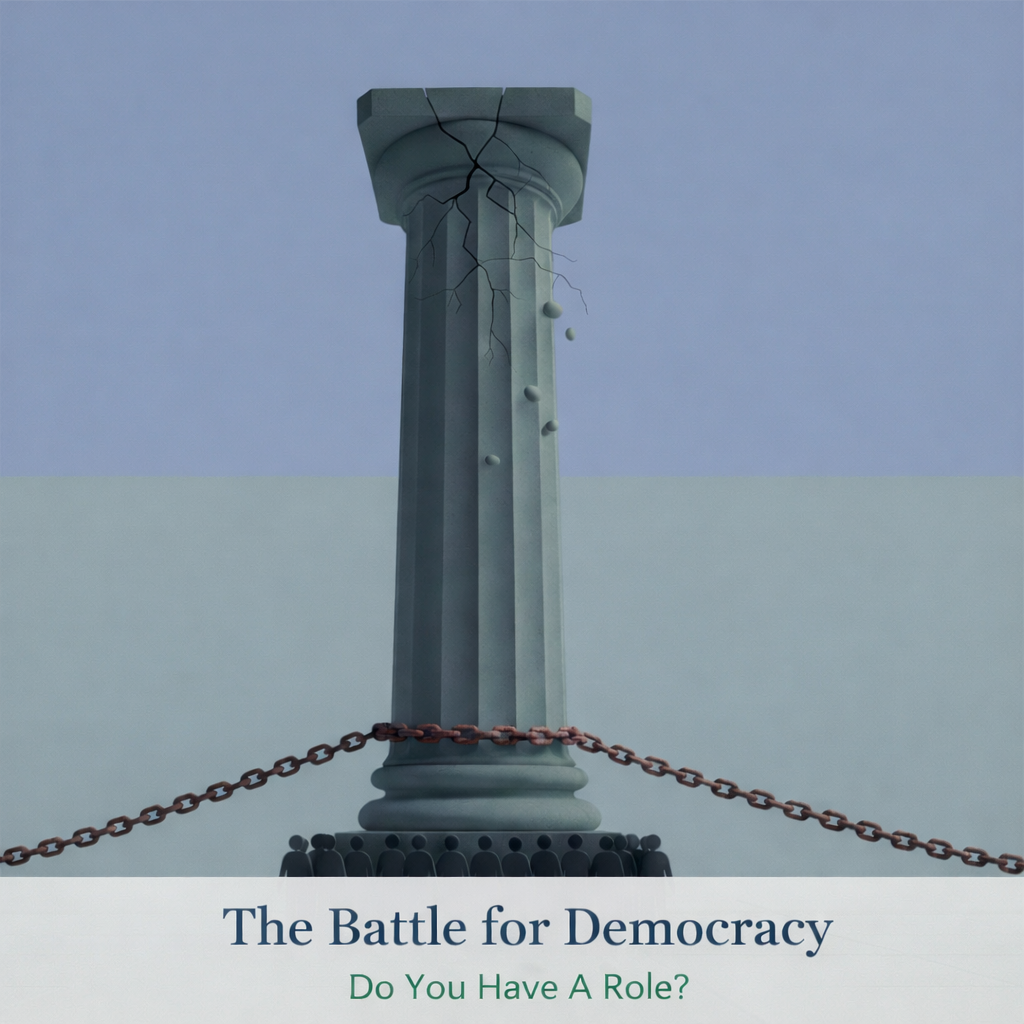

Authoritarian movements rarely end because of a single reversal. They end because sustained, strategic pressure makes continuation impossible.

Recent state-level pullbacks may feel like victories. At best, they’re Round 1.

As journalists like Rachel Maddow have emphasized—and as political scientist Erica Chenoweth has demonstrated empirically—authoritarian systems can collapse when a surprisingly small minority commits to prolonged, nonviolent, organized resistance.

Think “No Kings Day,” but sustained. Strategic. Relentless.

There’s no single magic script. But there are models worth studying—people who are using their professional skills, platforms, and credibility to do real work at a critical moment:

🔹 Sabrina I. Pacifici, MSLIS documents the erosion of science, public health, and the rule of law at LLRX.

🔹 Greg Siskind challenges unlawful and destructive immigration practices.

🔹 Gregory Miller advances transparent, open-source election infrastructure through the TrustTheVote Project.

🔹 Michael D.J. Eisenberg teaches lawyers how to use mobile phones and dash cams to document police misconduct.

🔹 Damien Riehl, Kara Peterson and Cat Moon have shown that petitions and coordinated legal action can matter more than cynics assume.

None of this is easy—or guaranteed—but the evidence suggests it works. History suggests it’s how turning points begin. Do what you can. But do something.

What is the best way that you or your organization can contribute?